Now that you have extracted your fossils from the rocks and transported it back to the lab, they need to be further cleaned and prepared. And of course there's the fun part of cataloging everything. All the information is derived from Orbis (1993).

Another tool palaeontologists use to remove dirt and dust is an air abrasive tool. This acts as a mini-sandblaster, blowing debris and matrix off of the fossil. Again, care must be taken to avoid damaging the fossil.

(Echioceras, (Bayle, 1878), an Ammonite from England)

After the fossil has been brought back to the lab and the various layers of plaster and packaging have been removed, the first thing to do is to fill out a condition report. This details any damaged or missing parts the fossil may have accumulated over time. This is important because knowing what is damage and what is actually part of the fossil is useful when it comes to describing the specimen.

(Darwinius (Franzen et al., 2009), a primate from Germany)

The next stage is to remove the surrounding layer of rock and dirt, called the matrix. Scientists do this by using a microscope and a pneumatic pen (basically a hand-held jackhammer). This has to be done very carefully to avoid further damaging the fossil.

(Tyrannosaurus (Osborn, 1905))

Unfortunately, breakages do happen. In order to fix any damage and to prevent further deterioration of the fossil, palaeontologists inject a special quick-drying glue. This will cause the bone to harden and fill any gaps that might cause structural weakness.

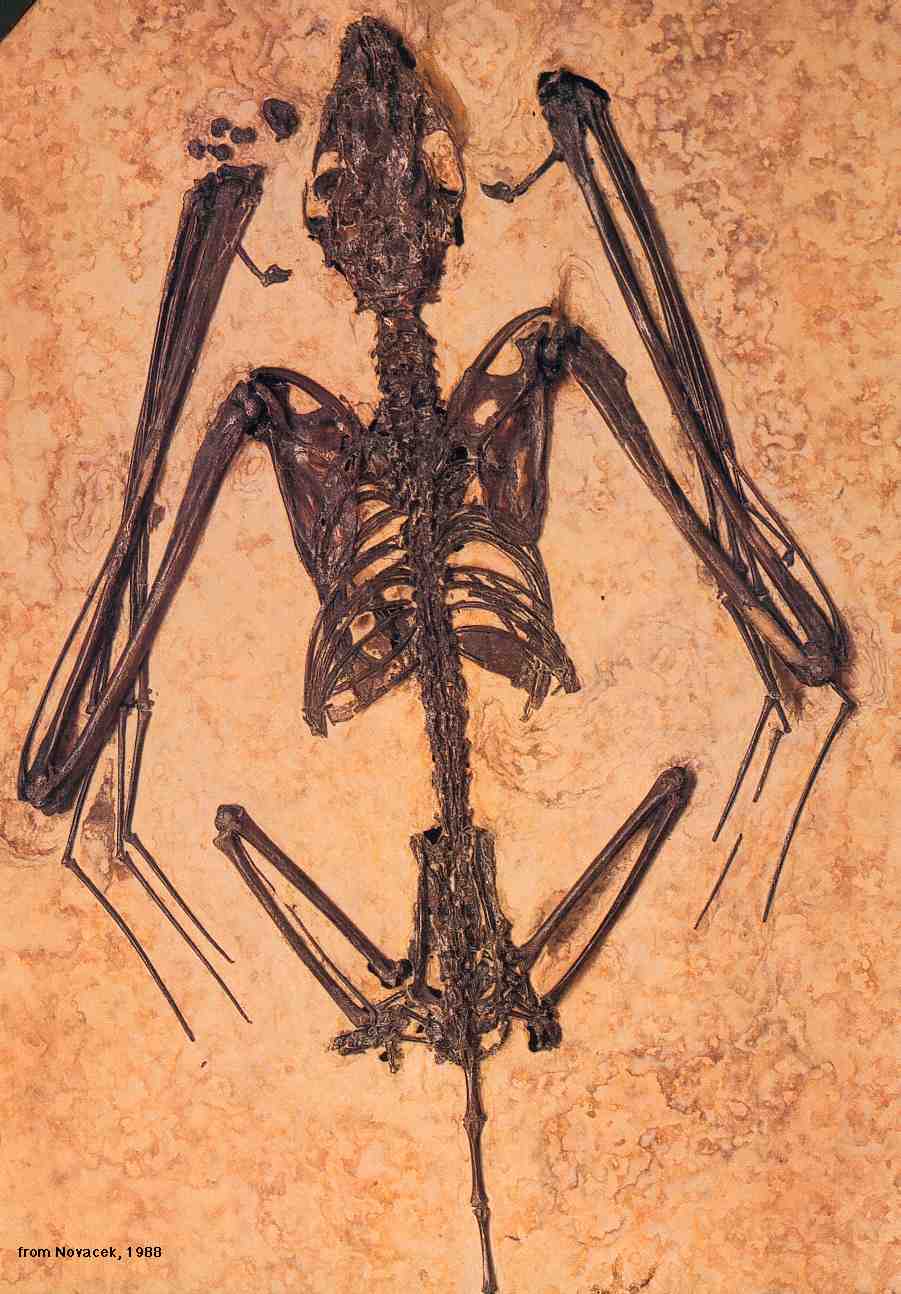

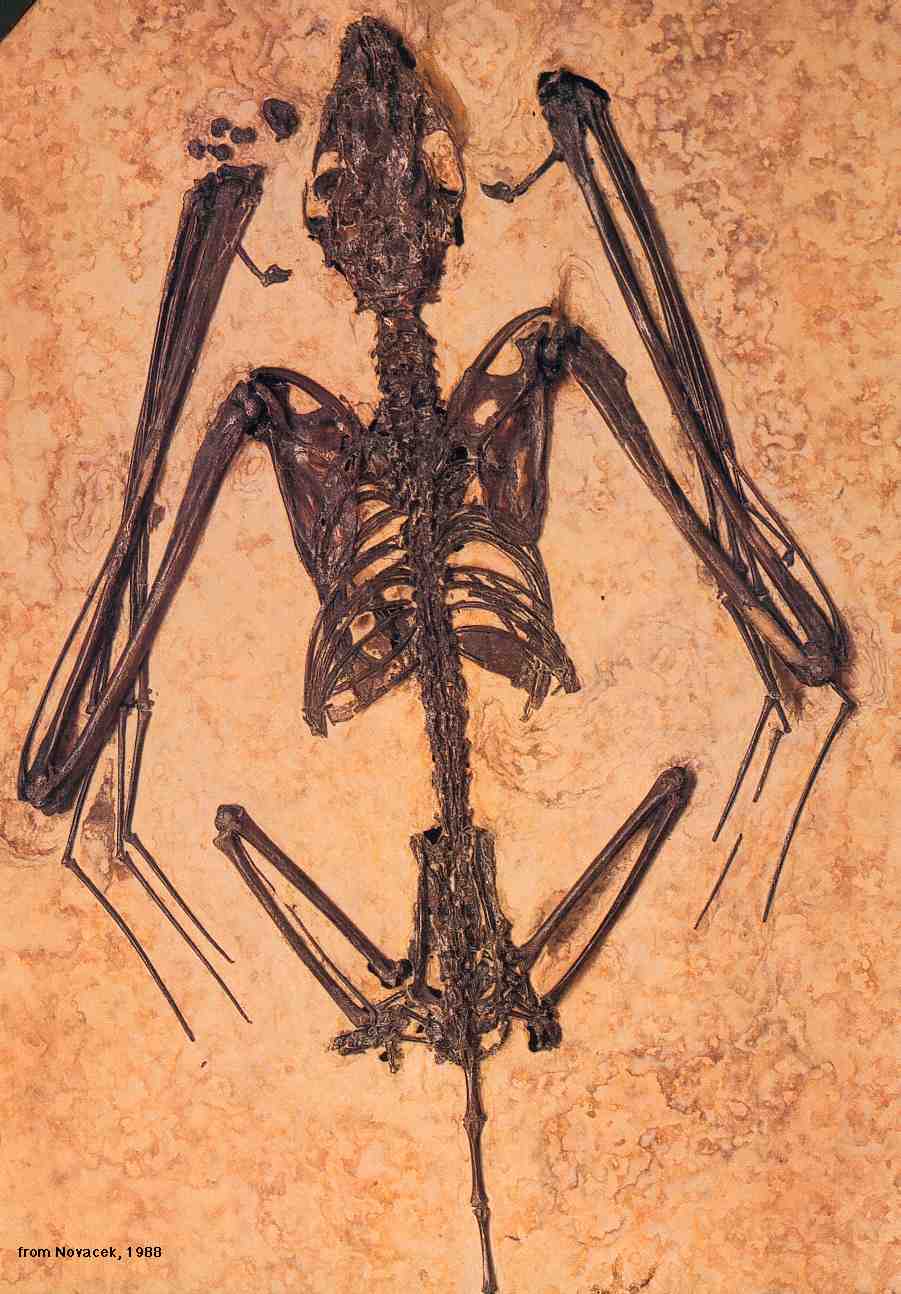

(Icaronycteris (Jespsen, 1966), a bat from Wyoming)

Sometimes, the matrix is too hard to remove with a pneumatic pen. In situations like this, an acid bath is used to strip away layers of rock. The acid used is quite weak and shouldn't damage the bone.

(Mene rhombea (Volta, 1796), a prehistoric fish from Italy)

Sometimes, the bones can be very dirty or dusty. Palaeontologists get around this problem by using an assortment of brushes. Water and mild detergents may be used but it has to be very delicately done.

(Meganeura (Brongniart, 1885), a prehistoric dragonfly-like insect from France)

Another tool palaeontologists use to remove dirt and dust is an air abrasive tool. This acts as a mini-sandblaster, blowing debris and matrix off of the fossil. Again, care must be taken to avoid damaging the fossil.

(Aeger elegans (Muenster, 1839), a prehistoric prawn from Germany)

Finally, just like the start of the lab process, another report needs to be filed, this time detailing what cleaning methods were used and what condition the fossil is in at the end.

Congratulations! You have now cleaned your fossils and they are now ready to be studied. The next step is to recreate the organism that your fossil is from. But that will be later. Next time, we will take a look at the life of another eminent palaeontologist: Edward Drinker Cope.

See also:

More dinosaurs

Discovering a dinosaur

See also:

More dinosaurs

Discovering a dinosaur

References

Bayle, E. (1878) Fossiles principaux des terraines. Service de la Carte géologique détaillée. Explication de la Carte Geologique de la France 4, part 1 (atlas), Paris: Imprimerie Nationale

Brongniart, C. (1885) 'Les insectes fossiles des terrains primaires, coup d'oeil rapide sur la faune entomologique des terrains paleozoiques', Bulletin de la Société des Amis des Sciences naturelles de Rouen, 1885 (1), pp. 50-68

Franzen, J., Gingerich, P., Habersetzer, J., Hurum, J., Von Koenigswald, W. and Smith, B. (2009) 'Complete primate skeleton from the Middle Eocene of Messel in Germany: morphology and paleobiology', PLoS One, 4 (5), e5723

Jepsen, G. (1966) 'Early Eocene Bat from Wyoming', Science, 154 (3754), pp. 1333-1339

Muenster, G. von (1839) 'Decapoda Macroura. Abbilding und Beschreibung der fossilen langschwänzigen Krebse in den Kalkschiefern von Bayern', Beiträge zur Petrefaktenkunde, 2, pp. 1-88

Orbis (2013) Dinosaurs! Discover the Giants of the Prehistoric World, 3, pp. 64-67

Osborn, H. (1905) 'Tyrannosaurus and other Cretaceous carnivorous dinosaurs', Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History, 21 (14), pp. 259-265

Volta, G. (1796) Ichthyolithologia Veronese

Brongniart, C. (1885) 'Les insectes fossiles des terrains primaires, coup d'oeil rapide sur la faune entomologique des terrains paleozoiques', Bulletin de la Société des Amis des Sciences naturelles de Rouen, 1885 (1), pp. 50-68

Franzen, J., Gingerich, P., Habersetzer, J., Hurum, J., Von Koenigswald, W. and Smith, B. (2009) 'Complete primate skeleton from the Middle Eocene of Messel in Germany: morphology and paleobiology', PLoS One, 4 (5), e5723

Jepsen, G. (1966) 'Early Eocene Bat from Wyoming', Science, 154 (3754), pp. 1333-1339

Muenster, G. von (1839) 'Decapoda Macroura. Abbilding und Beschreibung der fossilen langschwänzigen Krebse in den Kalkschiefern von Bayern', Beiträge zur Petrefaktenkunde, 2, pp. 1-88

Orbis (2013) Dinosaurs! Discover the Giants of the Prehistoric World, 3, pp. 64-67

Osborn, H. (1905) 'Tyrannosaurus and other Cretaceous carnivorous dinosaurs', Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History, 21 (14), pp. 259-265

Volta, G. (1796) Ichthyolithologia Veronese

No comments:

Post a Comment